AstraZeneca AB v Apotex opens the door to poisonous priority

The Patents Act 1990 (Cth) includes a provision for assignment of partial priority1 which was understood by many to avoid the problem of poisonous priority. However, poisonous priority was effectively introduced into Australian law in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd2. AstraZeneca (the patentee) amended the granted claims of their patent before entering into litigation with Apotex. The priority date of the patent was 26 January 2000, and the relevant claim amendment was made on 31 January 2005.

Because the court held that the claim amendment added subject matter that was in substance disclosed as a result of amending the specification, the priority date of the claim was called into question.

The patentee argued that the amended claim included different forms of the invention, including forms of the invention that were disclosed in the specification before the amendment, hence attempting to invoke partial priority to allocate different priority dates to different forms of the invention. If successful, this would have saved the claim from invalidity. However, the court did not recognise the claim as reciting different forms of the invention but rather mere variants of the invention and allocated a single priority date being 31 January 2005.

In such a case where the priority date of the whole claim is post-dated, new prior art may be brought into play. In the case of AstraZeneca3, the earlier publication of the actual specification became relevant prior art for novelty and thus the claim was held invalid for lack of novelty.

Interestingly, this case does not actually reflect the usual facts of a poisonous priority situation. It was however, the Full Court’s treatment of the provision for allocating partial priority4 which opened the door for poisonous priority in Australia.

Classic poisonous priority example

In light of the Full Court’s decision in AstraZeneca, theoretically at least, poisonous priority could arise in the following example:

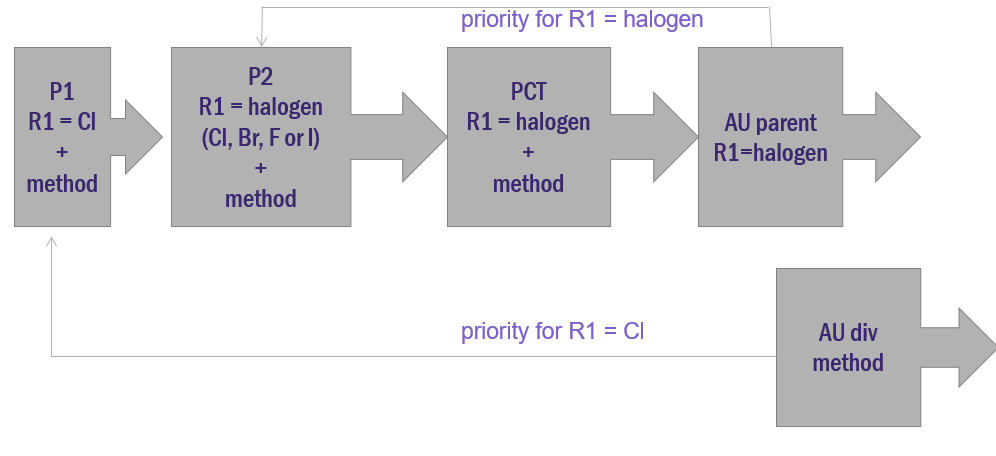

Priority application 1 (P1) is filed with a disclosure stating that R1 is chlorine, along with an accompanying method. At a later stage, the inventors discover through additional experimentation that R1 can be any halogen, not just chlorine. This information is added to priority application 2 (P2). A PCT application is filed claiming priority from each of the priority applications within 12 months of the first (P1).

At some stage, the PCT application enters the national phase in Australia, and a patent is ultimately granted with R1 claimed as being any halogen. For the purposes of this example, let’s say a lack of unity objection was raised during prosecution and necessitated the deletion of the method claims which could be pursued in a divisional application.

In this example, the priority date of the main claim in the granted parent would be the date that P2 was filed which enabled R1 being any halogen. This assumes treatment as per AstraZeneca where partial priority is denied. (Partial priority would have allocated the priority date of P1 for forms of the invention where R1 is chlorine, and the priority date of P2 for the forms of the invention where P2 is other halogens.)

The divisional application can thus be cited against the parent under ‘whole of contents’ novelty5. Whole of contents novelty exists where the cited earlier application with the earlier priority date (ie the divisional application) was not published until after the priority date of the patent under consideration (ie the parent). Under this technical subcategory of novelty, one could draft a notional claim in the divisional application based on the disclosure whereby R1 is chlorine. Such a notional claim would have a priority date back to P1 which is earlier than the priority date of the claim granted in the parent (that priority date is P2). As chlorine is a halogen, it becomes apparent that the notional claim of the divisional application, having an earlier priority date than the granted parent claim, contains information that would anticipate the main claim in the granted parent. Thus, a poisonous priority situation could arise.

Summary

The most important point to bear in mind is that the trap for poisonous priority is typically laid when the claim scope in a later filed application (eg P2) within a priority chain is broader than the claim scope in the preceding application (eg P1). The trap is triggered when a divisional application is filed.

Equally, a poisonous priority trap could be laid by making the PCT claim broader than the preceding priority application.

In part 2 of this series, we consider ways to avoid poisonous priority.

1 Patents Act 1990 (Cth), s43(3)

2 [2014] FCAFC 99

3 supra at 1

4 ibid

5 Patents Act 1990 (Cth), s7(1)(c) Schedule 1, definition of “prior art base”